| |

Ein musikalischer Spaß (A Musical Joke): Satire — and Tribute

An original yet highly problematic piece, WA Mozart's Ein musikalischer Spaß is a work I recorded with my ensemble L’Encyclopédie — and one that, I believe, is too often misunderstood. How does one approach it? Defend it? Without calling it a puzzle, I read a great deal about the work, only to conclude that it is, in fact, a simple and heartfelt mirror-tribute to a recently departed father.

Its four-movement form recalls a divertimento, with the unusual scoring of string quartet and two horns. Across this chain of oddities — horn dissonances, awkward orchestration, blatant harmonic “errors” and haphazard modulations, a surprisingly clumsy slow movement beginning in the wrong key and resembling an inelegant violin concerto (we worked extensively on this with our concertmaster, Gilone Gaubert), a painfully thin fugato and, finally, a wildly atonal cadenza to close the last movement — musicologists have long interpreted the piece as satire: a portrait of what a “bad” composer sounds like.

But this reading feels incomplete. Mozart the son achieved far greater humour elsewhere — not least in his operas. And why, at that time, would he even write such a work? The score is also remarkably difficult to play: as performers, we must be imaginative and persuasive to bring out its light-hearted spirit, staying true to the title. Spaß means joy, playfulness, mischief.

History itself, I believe, reveals the deeper meaning of the piece. On 28 May 1787, Leopold Mozart died in Salzburg. Less than three weeks later, on 14 June, Wolfgang completed this strange and original composition — one that was neither a commission nor intended for a specific concert. To my mind, it is clearly a pure and personal tribute to his father and to everything he transmitted to him — a homage sui generis. Showing how gauche a composer might be, without being gauche oneself, is no easy feat. The so-called “mistakes” unfold with a smile, bordering on an almost elitist satire. Left at that level alone, the work could seem like an austere inside joke.

But knowing that Leopold would have corrected these faults — kindly, lovingly — makes the piece human, tender, and deeply moving. It becomes a magnificent musical farewell. The son surely owed much to the author of the Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule (1756), the violin treatise that continues to inspire historically informed musicians today.

“What would I have become without my father’s teaching? Thank you, Papa!” — this is what the adult Wolfgang seems to whisper to us.

(May 2025)

***

Mozart: A Breath of Fantasy?

A certain tradition has decided that Mozart wrote only four Fantasias — an obvious mistake. The same tradition has otherwise established, precisely and exhaustively, the list of the Viennese composer’s works: sonatas, rondos, concertos, dances, and so on. Why, then, this unfortunate fate for the Mozartian fantasia?

Within this traditional musicological legacy, everything seems to suggest that Mozart was not — unlike Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach before him or the Romantics after him — an adventurer, an experimenter, a free spirit who did not need form in order to create music.

It is as if, in this view, such “fantastical” works did not represent Mozart, or at best belonged only to a minor corner of his output.

Thus, the very term “Fantasia,” because it implies a potentially dangerous informality — a territory with blurred borders and contours, unsettling for musical taxonomy — did not correspond to the image projected onto Mozart until very recently.

Is it not often said that Mozart had no true heir in music history because he had achieved a perfection of form and aesthetics beyond surpassing? According to this narrative, it is Haydn who leads to Beethoven, and Beethoven who in turn explains the further evolution of Western music up to today. Mozart’s work would therefore represent a break in continuity: a sublime aesthetic dead end, a perfect cathedral, a citadel almost untouchable.

The “Mozartian dead end” is very likely not the one we think!

If it was the composer’s own wish to complete a given piece, why should the Mozart fantasia not be regarded as a fully conceived, fully realised work in its own right, rather than a supposedly “inferior” musical form, a sketch or draft? Charles Rosen speaks in these terms about the famous Fantasia in C minor, K. 475. He questions the validity of imagining a Mozart fantasia as merely formal experimentation, somehow below his other compositions. In doing so, he questions the place these works occupy in the composer’s imagination: is the fantasia a realm of freedom, often virtuosic for the performer, where the composer experiments with multiple forms at once? Or is it rather a way of pushing his compositional virtuosity to the extreme, outside the formal codes in which we so readily recognise his style — and in which he is most expected?

If musical rhetoric teaches a hierarchy of genres, and if tradition sees Mozart as the great champion of perfect musical forms — even in opera — there has never been a specific place granted to this part of his output. It has often been judged anecdotal and consigned to the category of “miscellaneous works.” And yet, because it plays a bigger role in his oeuvre than is usually acknowledged, the fantasia deserves to be examined afresh today.

It also raises questions about how Mozart himself regarded these works. Some Fantasias are unfinished, such as the D minor Fantasia K. 397, completed by his pupil August Eberhard Müller. The C minor Fantasia K. 396, written for pianoforte and obbligato violin, was reworked by another pupil, Maximilian Stadler. There is also the completely unfinished F minor Fantasia K. 383, to which we will append — for harmonic and stylistic reasons — an isolated movement from a sonata in G minor (K. 312), a fragment of an F minor Fantasia ending on a striking G major chord. The Modulating Prelude K. 624, for its part, was marked “unfinished” purely by accident: the two parts of its manuscript were separated for decades, and its second part was at times even classified among Mozart’s piano concerto cadenzas!

Beyond the fragmentary nature of this corpus of Fantasias lies the question of publication. Because most of them are unfinished, it is highly likely that Mozart never intended to publish them. While the Fantasias mentioned above — as well as the Prelude and Fugue K. 394, sent to his sister in 1782, and the Modulating Prelude K. 624 from 1777/78 — long remained in the shadows, the first Fantasia to be published was in fact K. 475, coupled with the Sonata in C minor K. 457. It appeared with Artaria only in 1785, at a mature stage in the composer’s life.

An interesting anecdote: that same year, 1785, a concert programme from a Masonic lodge mentions the “Phantasien” performed by Mozart, including the famous K. 475. Even without publication, these inherently free works corresponded perfectly to the open spirit of the lodges — an exaltation of continuous, liberated musical thought, freed from formal constraints. Was the fantasia, during that evening of initiates, the symbol of a certain Enlightenment mindset? The mystery remains as to the programme’s exact content.

In any case, in the year of his death, 1791, Mozart published another Fantasia, this time for two keyboards in F minor (K. 608). It is striking that a piece originally written for a mechanical clock-organ should become a fully fledged, lyrical work — with such an expressive second movement! — reworked by Mozart for four hands and later transcribed by his contemporary Muzio Clementi for two hands. The life of a fantasia, perhaps? Such arrangements were common practice at the time, though this particular one has never yet appeared on disc.

Why, then, did Mozart wait so long to publish his earlier Fantasias and Preludes? Expansive, virtuosic works with memorable melodies flowing one into another between swift cadential passages — they are, after all, full of charm.

Because they were often neither private nor editorial commissions, because they were not regarded as “standard pieces,” and perhaps also because they require from the performer both solid technique and a real command of musical rhetoric, Mozart did not cultivate them systematically — nor did he imagine that such works might contribute to his success as a composer.

All of this makes the project of bringing together these free, “unclassifiable” works on a single album especially exciting. It demonstrates that Mozart is not a composer of formulas, nor simply a formalist mind, but one who throughout his life ceaselessly questioned form, style and genre through these discreet and still little-known works — works in which a true musical revolution was already taking place.

(September 2024)

***

let's talk about Mozart's cadenzas again...

Last but not least, thanks to a concert I have just given with my Ensemble de L'Encyclopédie, a few thoughts on this "improvising" spirit of Mozart's cadenza came into my mind. This Concerto for pianoforte and orchestra n°20 Kv 466 has been played for generations with cadenzas written by Beethoven, those of Mozart missing.

I have always found since I was a teeanger that these cadenzas by Beethoven were out of style, not without a certain snobbery that one can have at that age; Laurent Cabasso, my teacher at the time, had me work on this concerto at the age of 15, and at the time I had written cadenzas that were far too "romantic" to be honest. Question: should we be stylistically "in tune" with Mozart? Or responding to a certain tradition (i.e. playing by tradition Beethoven's own cadenzas)? Should the performer solely be "of his time" (Hummel, Brahms and Reinecke published their own cadenza of this concerto)?

There are beautiful examples of cadenzas, like those of Malcolm Bilson in this concerto... I say "beautiful" according to my canons of beauty, and my "cadenza" expectations... I did not want, in the realization of both cadenzas of the first and third movements, to soften the dramatically perfect language of this concerto so that I could express my art of being a soloist, but I'd rather integrate a cadenza as a modest patch of color that would highlight the qualities of the incredible work that is this Concerto Kv 466: correct duration of the cadenza, expression of Mozartian intertextualities (d minor tone found in his masterpieces Don Giovanni or the Requiem), missing rhythmic figures (the triplet in the first and third movements), use of the potentialities of the pianoforte "come si faceva" (moderator and forte pedal use)...

It is true that in the light of what pianofortists like Paul Badura-Skoda, Robert Levin or Malcolm Bilson who have contributedso much in terms of improvisation, "diminutions", cadential writing, my priority has been to musically react in a truly "concertato" dynamic : the exchanges between orchestra and solo instrument have perhaps never been so well distributed as in this concerto and open the way to new questions, particularly on the agogic which will doubtless question me for a long time to come.

(December 2022)

*****

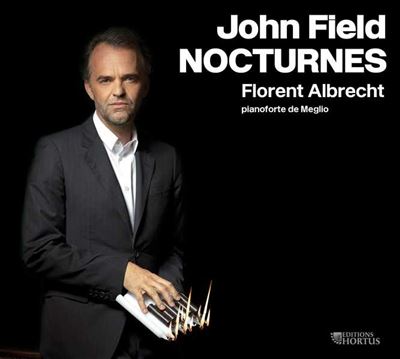

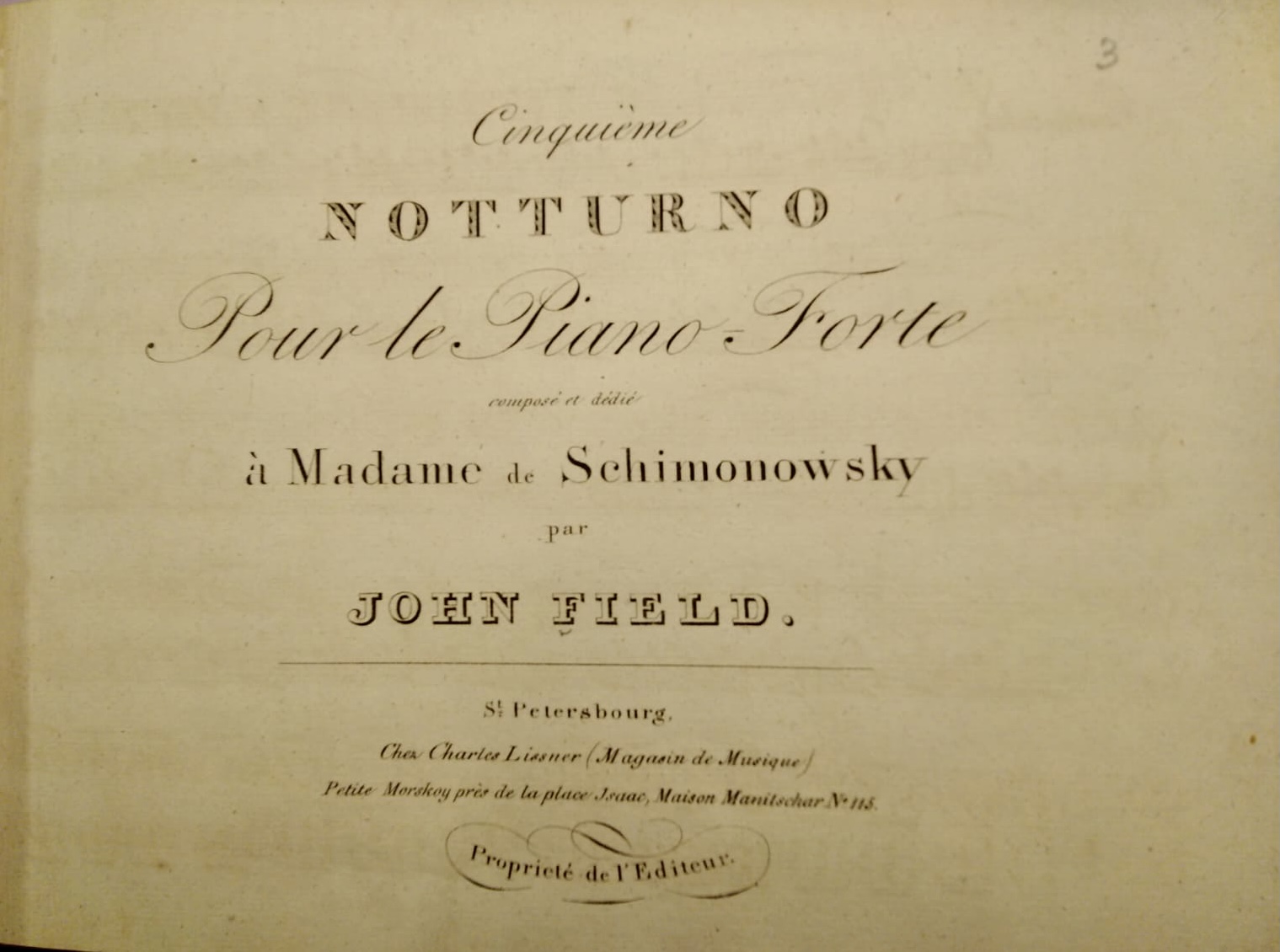

Performing John Field’s Nocturnes Today : memento of my wanderings-about…

When I chose for my first solo release to record the complete Nocturnes by John Field, I hadn’t yet come to grips with the scope of the task awaiting me. I was familiar with a few recordings, on modern pianos or with pianoforte, and the score struck me as being of irregular complexity and richness, whilst at the same time, because challenges have always guided me in my musical choices, it seemed to me that this programme perfectly suited the Carlo de Meglio pianoforte, an original Neapolitan instrument from 1826 refurbished by Ugo Casiglia, which I had acquired during the automn of 2019. I soon discovered that Field’s last European tour, during which crossed paths with a number of young musicians such as Liszt or Chopin, concluded in Naples, where the instrument was to be found at the Bourbon Court; but he did not play it, exhausted by his bout with illness.

Liszt, to whom we owe the only ‘complete’ edition of Field’s Nocturnes in 1873, took note in his preface of the extreme amateurishness of John Field in matters of publication of his own works, as if he ultimately couldn’t have cared less about his posterity: Liszt made light of the problems in getting hold of the manuscripts, of the first editions of these Nocturnes, some of which had been published initially with other titles (‘Rondeau’, ‘Pastorale’); the harmonic and even melodic errors unworthy of a composer of his stature; the ‘fake’ posthumous Nocturnes given that title by a publisher with a flair for a fad in this unique, pianistic form that the composer had made into a staple all over Europe. A far cry from today’s Urtext editions – cruelly lacking today in the case of Field – Liszt’s also contains errors, approximations… and, at the least, aroused suspicions on my part, questionings that led me to set out on a search through European libraries for the earliest editions: the British Library in particular possesses the first Franco-Italian Carli editions that enabled me to assuage my wondering about this or that phrasing, here or there a missing or faulty chord, a particularly strange-sounding note… The most significant error in Liszt’s edition remains in my view the improper, systematic indication of the pédale harmonique, which means that it reacts solely in terms of the harmony. The young Chopin, accustomed to Viennese instruments up to his arrival in Paris at the end of the 1820s, makes use in his youthful works of this device known as the ‘atmosphere’ pedal, which can last the full length of a phrase, and contributes to an intentional harmonic blurring, conceivably a ‘register’ of the instrument if you will. Field’s favourite piano was a Tiesch, of which apparently only one or two examples exist in the world today, and which had a Viennese action, that is, an instrument whose lightsoftharmonics allowed such a use of the pedal, and even a perpetuation of this use over time.

The unpublished Nocturne, brought out in 1829 by the Moscow Revue of Music, of which I was aware but had considerable trouble locating before coming across it in the Saint Petersburg Library, is clear on this point: the forte pedal is never harmonic therein, but is an expressive medium that blurs the sound over entire phrases.

Hence my choice was to reinstate to the extent possible a ‘manner’ in which the Nocturnes by Field must have existed. In concrete terms, the choice of my Meglio pianoforte with its Viennese action was a foregone conclusion: the composer’s departure from England for Russia in 1803, at the age of 21 years, in no way mandated, whether historically or esthetically, the choice of a Broadwood or Clementi – the composer was his own mentor, and an instrument builder as well, which could have rendered the use of the forte atmosphere pedal moot.

I also decided to delete from the edition made by Liszt the last two Nocturnes, neither of which had been such a title by Field in his lifetime.

Stylistically, in addition, I have long been cultivating an innovative project for interpreting these pieces: not that I felt absolutely obliged to seek out novelty in absentia/ex nihilo/for novelty’s sake, which would have been presumptious on my part. But it has always seemed to me that these Nocturnes by Field have been interpreted in light ofChopin. This in my opinion leads to an error in style, indeed to a historic non sequitur. The similarities between Field’s 9th Nocturne and Chopin’s no. 2 op. 9 are salient; no less so are Field’s novel approaches in the area of instrumental technique, such as the use of the thumb in the 7th presaging Chopin’s contributions in this domain a few years hence. The lure of a certain vocality claimed for their instrument, the influence of the bel canto cantilenaand of simple but directly expressive melody constitute further compelling parallels between the two composers, and Field’s influence on Chopin may readily be felt. Chronologically Field was brought up tellingly in the grand tradition of musical rhetoric, at a time when talk was more of the Fine Arts than of Art, wherein what counted was expressing a direct, simple, almost ‘landscaped’ feeling. This is how Guy Sacre puts it, in the era during which John Field was composing his Nocturnes, between 1812 and 1835, at a moment when ‘the piano, on the strength of its mechanical progress, //took upon itself to rival the voice in ‘cantability’, in expressivity, in ‘emotion’, to invent ‘a genre in which to pour out the heart, in the manner of a vocal romance’. In Chopin’s ‘pure’ music, not so much descriptive of a state of mind as focused on the expression of a feeling within the musical space that witnesses the playing out of each of his intimate psychological dramas, the musical notation leaves little freedom to the performer, being ultraprescriptive. With Field, the first goal is of emotional essence, and its expression proceeds via an adaptive understanding on the part of the performer vis-à-vis the rhetoric, the bel canto-inspired vocal model implying a particular rubato: all the more as the era’s pianofortes, with their Viennese action, have highly tense trebles, as opposed to the Chopinian Pleyels from 1830 onward. The point is to compensate, as it were, the lack of natural sound by a playing technique consistently in the service of melody and music, rubato being one of the means of highlighting this or that melodic climax.

Everything comes about as if, with Chopin, the performer had embarked on paths with frequent signposts hewing closely to perilous cliffs and, having once put the pitfalls behind, coming upon complex panoramas of staggering beauty. With Field, it would be little paths through the undergrowth, pleasant and simple, at times hard to cut through, at times thorny, somewhat labyrinthine in their apparent simplicity, where in one can easily become lost and could make do in case of a desire to have a friendly picnic; it’s up to the performer to use his/hercompass, taste and knowledge, to find in these hidden landscapes the path – and it does exist! – leading upward to that promontory where, like a shepherd on his rock, hehe or she will be able as well to contemplate exquisite beauties.

(Trad. K. Lueders for Hortus)

(september 2021)

*****

CADENZA for Mozart's 25th PIANO CONCERTO Kv 503

For the first concert of my dearest Ensemble de L'Encyclopédie, in October 2020, violonist legend Chiara Banchini and myself decided to think of an ambitious program "of the Enlightment" : such as one could listen to at famous Concerts Spirituels in Paris in the second half of the 18th century.

In that program, Mozart's 25th piano concerto Kv 503 was original in that sense that the composer did not write a cadenza for any of its movement : a cadenza is like a "cerise sur le gâteau" passage where the soloist kind of improvises on melodic themes with some virtuosity! I wrote mine imagining what was possible to be listened to, according to Mozart's style, taste, and my own sensibility... how daring to use a theme of French Marseillaise!

(June 2021)

DOWNLOAD THE CADENZA

*****

FROM CANTABILE TO RUBATO, THE PIANOFORTE, SPIRIT OF THE CENTURY AND COMPANION OF THE SOUL ...

Today, we hardly hear anyone questioning the authority and existence of the pianoforte as an instrument in its own right and not as a historical "transition" between the completed form of the harpsichord and that which we know. Since around 1880 - date of the appearance of the first concert Steinway - the modern piano, it took decades of legitimation and battles.

Pianoforte players such as : Paul Badura-Skoda, Malcolm Bilson and other non-pianofortist musicians from elsewhere were discoverers, "enlighteners" according to the Baudelairian expression, in matters of historically informed interpretation as quoted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Anner Bylsma, Gustav Leonhardt, and others still!

An innovative approach to interpretation from the 1960s included both the instrument, score and the comprehension of musical essays in order to offer a dynamic and critical reading of music and the weight of its traditions, always pushing forward the work performed in concert rituals which harmed it more than served it.

" Brightness without meaning puts me off!" Affirms Nikolaus Harnoncourt, sweeping away more than a century of traditions and rituals of so-called "classical" music. The result today is that we don't play Mozart like we did 40 years ago; even the great symphonic phalanges can no longer be blinded by the weight of tradition regardless of the type of repertoire approached. The place of the pianoforte, in these decades of slow aesthetic upheaval of performances, organology, the vision of works and the ritual of the concert, is apart. As an instrument, the pianoforte has a "life" in the History of Music which is ultimately rather short: from 1760/70 - that is to say when composers like Mozart or CPE Bach really write for it, and therefore really give it life until 1880 which saw the development of the famous Steinway. These are only theoretical historical fringes, but which remain quite enlightening.

Paradoxically in the organological field, no other instrument has known such a boom in such a short period of time. So many artistic innovations, patents and new experiences, supported in the life of composers and performing musicians, have allowed an artistic emulation like never before. Better than that, the pianoforte carries within it the seeds of a musical revolution. It is the instrument of possibilities, built little by little industrially to invade bourgeois and aristocratic salons. The consequence of this has been to democratize a certain relationship to music through and beyond social classes.

The pianoforte is the instrument which allows the composer, with each widening of the keyboard, to go further, to test the musical possibilities: we see it with Beethoven or Chopin, who use all the space of the keyboard and as the pianofortes they play.

Each composer, from Mozart to Fauré via Brahms, Beethoven, Liszt, Chopin, Schubert, and the minores (Steibelt, Adam, Moscheles, Hummel, Dussek etc.) have brought so much to the world of the pianoforte and the modern piano by ricochet.

The pianoforte is undoubtedly a multifaceted instrument, from the first steps of Cristofori at the dawn of the 18th century, through to the innovations of Silbermann in Strasbourg, despised and then loved by JS Bach shortly before his death in 1750. With the prolific development in England, France, Austria etc. one cannot imagine how much the pianoforte is not "one" but that it takes on a multiplicity of realities. In the 1800’s in France alone some 200 piano manufacturers each put their name on the construction of the pianoforte. In the world today there are maybe ten or so pianoforte manufacturers at most!

The pianoforte’s fortune in the 19th century undoubtedly became a victim of its own success where one finally spoke more of the performer, one remembers "I am the concert" Uttered by Liszt following a concert, feeling invested with a limitless romantic and egotistical genius. The instrument became secondary until the advent of the modern Steinway, by making a certain type of listening standard and therefore leaving an ever-so important place for the performer who gives a work to listen to and no longer engages in a dialogue with a uniquely coloured instrument (consider a violinist with his instrument). The Steinway did not only kill the pianoforte, it has, like the ashes of Vesuvius on the city of Pompeii, been frozen under clouds of stereotypes and clichés which endured. There are exceptions of course, we remember Richter taking his Yamaha around the world, like Horowitz his Steinway; Pollini today doesn’t travel without his own Steinway… and his technician!

It is undeniable that the movement which has affected music as a whole under the aegis of these revolutionary "baroque" has been slower in the case of the pianoforte. What is this due to? Listen to the last of Beethoven’s Sonatas recorded by Badura Skoda in the 1970s / 1980s… just sublime. However, I myself as a pianofortist have had a hard time listening to them because this instrument is very wrong, too wrong for my ears. My feeling is biased by this strange feeling in my head which tells me: this is a historically informed version, carried by the critical dynamic of the work, the instrument, etc. but while harpsichords are tuned "right", admittedly according to temperament, why should a pianoforte sound "wrong"? In other words, could of Beethoven considered an untuned instrument in his time worthy of his art?

The composer Louis Adam wrote at the beginning of the 19th century in his pianoforte method: "The Pianoforte is of all instruments the most widely cultivated". It is true that by studying the scores; listening to the recordings of the great masters of the (modern) piano; adopting a humble "researcher" approach, we will never know how Beethoven wanted us to know how to play his Sonatas. I offer myself as a pianofortist the dynamic and always live, present day possibility of questioning myself and to pose "options" of interpretation in conscious and deliberate acts.

Because this is also the approach of the "historically informed" performer: asking questions that go naturally against what has been given as information, and in favour of your own research. To come back to this Badura-Skoda recording, it seems to me that even in the 1980’s, despite the quality of these "giant" performers, we have not reached the level of pianoforte manufacturing that we find today. Manufacturing masters like Christopher Clarke, Emile Jobin, Ugo Casiglia have reached new heights in terms of technical understanding, repair, construction of the pianoforte ... when they don't build replicas, they renovate genuine instruments and continue to discover the unique and almost hieroglyphic mysteries of each instrument, to scrutinize the soul of each of them, to bring them back to life and allow the performer to reconnect with them. What a mission!

The magic of the pianoforte is that it rekindles the relationship of the manufacturer to the performer. Of the performer to the instrument and enriches the dialogue between the performer and the music with a dimension that is both human and undeniably intellectual. I remember playing in Paul Mc Nulty's workshop, fascinated to see that he was not listening to me but listened to the instrument ringing under my fingers, and smiled silently at what I could understand from this instrument, by the way I made it sound, as if there were a secret and infinite bond that united the three of us. Today, as a pianofortist, I hope to transmit in concert not only my interpretation but also a quality of the instrumental sound that highlights the work through me, and the instrument through the performed work. Such a richness!

The interest of the pianoforte today is that of famous musicians, alongside the instrumental construction, and the incessant progress of musicological research which has evolved a lot over the past 40 years. The young pianofortists: technically stronger, more aware and informed, curious and educated by a paedology, have benefited from a favourable ground for working on the instrument that do it justice. It is wonderful to see a new generation of pianofortists with their instruments on the most beautiful of international stages and making an often-astonished audience discover all the potentialities of the instrument, the classical cantabili, the romantic rubati.

I recently gave a concert with my ensemble in Geneva, whose 18th century program was built according to this aesthetic of the varieties dear to the Concert Spirituel, with movements of various works of different genres.

I thought while speaking to a journalist of the tremendous power of my instrument that evening - a copy of Walter pianoforte built by Monika May -, and, strangely, it was not something that I had consciously "calculated": from the continuo to chamber music pieces, I still preluded between two orchestral works, until my role as a soloist in Mozart's concerto kv 503. Playing the pianoforte throughout the concert, I unwittingly erected a new relationship between my instrument and myself, a rather enjoyable relationship for me as a performer not isolated in a function, but in constant dialogue both with my fellow musicians, my instrument and the audience. I then found a real sense of what it is like to be a musician !

(November 2020)

|

|